A symbol, a trope, a hallmark, a cliché – call it by any other name, the airship is inseparable from Dieselpunk. Our alternative skies are full of dirigibles, real and unreal, peaceful transports and dangerous battleships. These giants can be seen as the ultimate expression of Diesel Era spirit and, at the same time, of contemporary retro-futuristic vision.

![]()

LZ129 Hindenburg. May 1937

The most famous airship career ended in a disaster. But the Lakehurst explosion was probably the saddest episode in a long chain of disasters, and the Hindenburg was the largest and most luxurious of many Interbellum airships, some of them well forgotten. Let’s see what we can incorporate into our Dieselpunk setting.

Look at this picture taken in 1936:

![]()

LZ129 Hindenburg on her inaugural flight between Freidrichshafen and Lakehurst

In the upper right part of the field there is another airship, USS Los Angeles, née LZ126. Built by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH in 1923-1924 and handed over to the United States as a part of war reparations, she has a distinction of being the first German-built dirigible to cross the Atlantic. The Los Angeles (ZR-3) served with the U.S. Navy until 1939.

But the LZ126 was not the first zeppelin built in Germany after WWI. In 1919 and 1921, two civil airships, the Bodensee and Nordstern, were commissioned by DELAG for passenger flights between Friedrichshafen, Berlin and Stockholm.

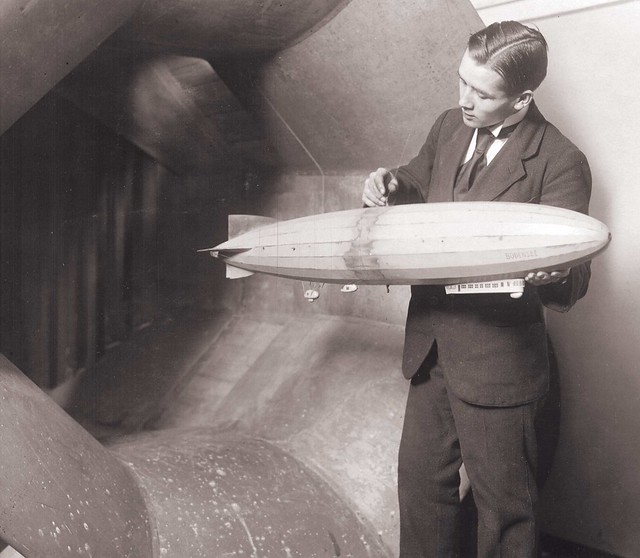

![]()

Wind tunnel testing of design for LZ120 Bodensee. Via Mr. Yuri Gagarin @ Flickr

The first one entered service, the second made her maiden flight just in time to be seized by the Allied Control Commission. Both were ceded to victorious powers and renamed: the Bodensee upon arrival to Rome became Esperia, the Nordstern received a French name, Méditerranée.

![# 0 1 dix2]()

French Navy airship Dixmude, ca. 1923. Jean Duplessis collection

The French already had the world’s largest airship, ex-German LZ114/L 72 renamed Dixmude. Her service was short: on December 21, 1923, she was lost with all hands (44-man crew) between Sicily and Tunisia.

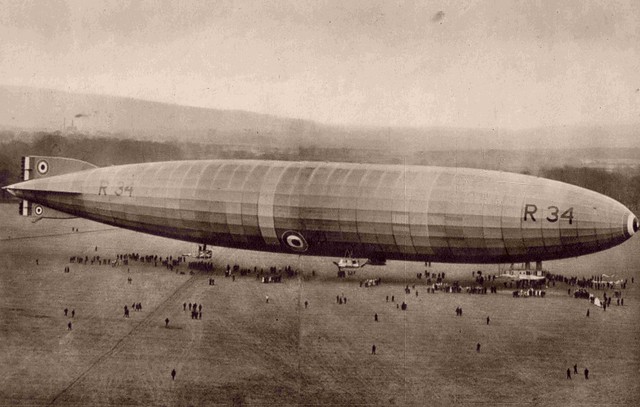

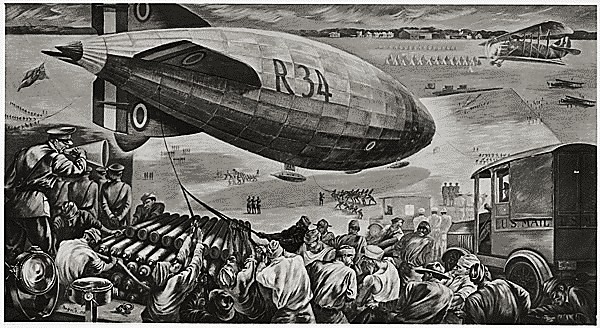

![]()

R34, the first airship to make a round-trip flight across the Atlantic. Via old school paul @ Flickr

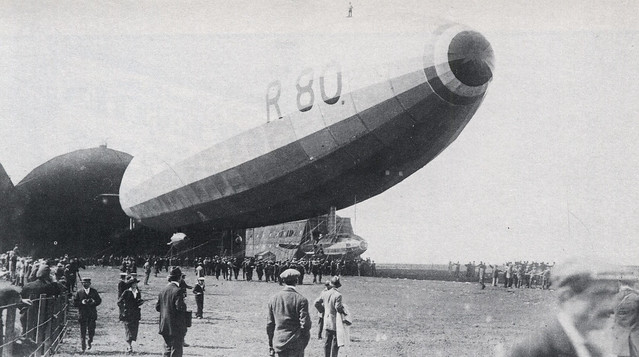

In the meanwhile, the Britons continued to build their own airships, making good use of the captured German technology. Here is the unsung and short-lived R80 designed by Barnes Wallis and HB Pratt:

![]()

The R80 airship at Barrow in Februrary 1920 via Plaxton Fan @ Flickr

Too small for her intended airliner role, she has a brief service as a crew trainer, then her airframe was used for destructive tests on components and she was finally dismantled in 1925 after 4 years, having flown for a total of 73 hours.

In the meanwhile, a new airship power was emerging – the United States of America. Prior to developing their own designs, the U.S. Navy used foreign-built airships.

![]()

USS Roma (originally T34), the world’s largest semi-rigid airship. Purchased from the Italian government in 1921. Crashed during test flights on February 21, 1922

![]()

British-built R38. She was bought in October 1919, but crashed in 1921 before the U.S. Navy could take delivery of her and did not officially receive its US designation, though she was painted in accordance of its planned Navy designation. The U.S. Navy Archive via lazzo51 @ Flickr

In 1924, with the arrival of LZ126, the Navy finally had a reliable large airship, capable of long-range transport and reconnaissance missions. Short before that, the first US-built rigid airship, the Shenandoah, started her naval service.

![]()

USS Shenandoah moored to USS Patoka. Image via airships.net

On September 3, 1925, on its 57th flight, Shenandoah was caught in a storm over Ohio and lost. 14 of the crew, including her commanding officer, Commander Zachary Lansdowne – were killed. The crash was a major setback for the US airship program, advocated by Rear Admiral William A. Moffett.

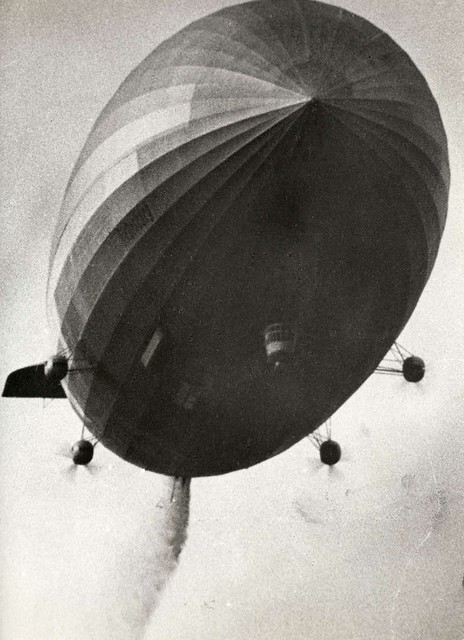

At the same time, Italy started to build a series of semi-rigid airships designed by Gen. Umberto Nobile. The first of the series, N-1, was made available to Amundsen Polar Expedition. Renamed Norge, with Nobile at the controls and Italian crew, the airship reached the North Pole on May 12, 1926.

![]()

Norge – the first aircraft to fly over the polar ice cap between Europe and America. Via :ray @ Flickr

Two years later, Nobile’s own arctic flight on the Italia, an enlarged and improved version of the Norge, ended in a crash.

![Stolp, Landung des Nordpol-Luftschiffes "Italia"]()

Italia en route to the Pole. Stopover at Stolp, Germany (Bundesarchiv)

An unprecedented international rescue effort helped to save most of the crew. There were casualties among the rescuers, too – Roald Amundsen who flew on a Latham 47 seaplane to search for his Italian friend, disappeared together with the crew of five French Navy servicemen. It is believed that the plane crashed in fog, and that Amundsen was killed in the crash, or died shortly afterwards. His body was never found.

Umberto Nobile survived but failed to receive new funds from the Fascist leadership. In 1931, he went to the Soviet Union where he worked until 1936, helping to develop semi-rigid airships. Some Soviet designs, most notably the V-5 and V-6 dirigibles, were obviously influenced by Nobile N-series.

![Vassily Kuptsov. Dirigible. 1933]()

Vassily Kuptsov. Dirigible. 1933

The airship shown above is the ill-fated CCCP B-5 (USSR V5). Built in 1933, she was dismantled in 1934 – her ‘envelope’ was leaking and generally unreliable. While a new ‘envelope’ development has been in progress, a lightning struck hangar near Moscow where parts of the dirigible were stored. Everything went down to ashes, not only cases with B-5 parts, but her sistership B-4 (also dismantled) and a brand-new B-7 as well.

![]()

The Dirigible Memorial erected at the burial site of 13 crewmen perished in the crash of the SSSR-V6 OSOAVIAKhIM (February 13, 1938). In October 1937, the V6 under command of Ivan Pan’kov set a world record for airship endurance of 130 hours 27 minutes, beating the previous record set by the Graf Zeppelin.

![#0 1 a 01 0air pobeda 1]()

Later Soviet design – the Pobeda (Victory) was built in 1944 and later used to transport cargo, mainly hydrogen for balloons used to train paratroopers, on short routes from 20 to 500 km. The Pobeda crashed on 29 January 1947, killing her crew of three airmen.

Back to Germany. On September 18, 1928, LZ127 Graf Zeppelin, the future Diesel Era icon, made her first flight. Since then, it was a success story: nine years of sterling service, over a million miles flown on 590 flights, thousands of passengers and hundreds of thousands of pounds of freight and mail, fast and safe.

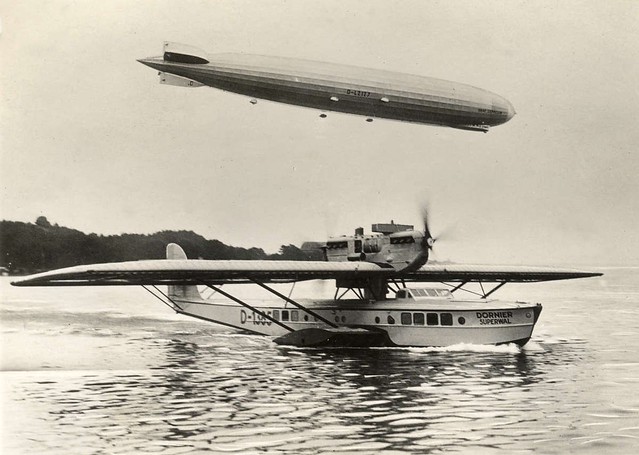

![]()

LZ127 Graf Zeppelin & Dornier Superwal. 1928

To commemorate the Graf Zeppelin premiere, Prussian State Mint struck a medal with two profiles:

![]()

Zeppelin medal, 1928. Graf Ferdinand von Zeppelin and Dr. Hugo Eckener, the manager of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin and the LZ127 commander

Famous promotional photographs:

![]()

The Graf Zeppelin, dining room

![]()

The Graf Zeppelin cabin

Next year, on December 16, another giant airship took off – the British R100 built by a subsidiary of Vickers-Armstrong for commercial use on British Empire routes. In July 1930, the R100 made her Transatlantic flight, reaching the Canadian mooring mast at the airport in Saint-Hubert, Quebec in 78 hours having covered the great circle route of 3,300 mi (5,300 km) at an average speed of 42 mph (68 km/h).

![]()

R100 in Toronto. Via Kemon01 @ Flickr

The airship stayed at Montreal for 12 days and over 100,000 people visited the airship each day she was there, and a song was composed by La Bolduc to commemorate, or rather to make fun of, the people’s fascination with R100. She also made a 24-hour passenger-carrying flight to Ottawa, Toronto, and Niagara Falls while in Canada. The R100 departed on her return flight on 13 August, reaching Cardington after a 57½ hour flight.

![]()

R100 remembered in 1936. Via Smile Moon @ Flickr

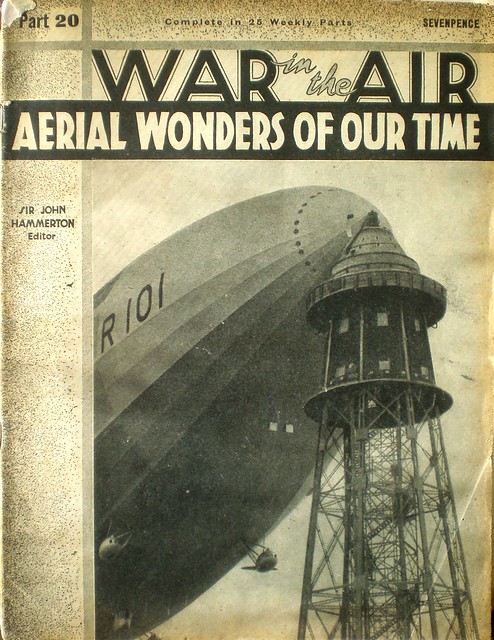

The other British Airship, Air Ministry-designed R101, made her maiden flight a bit earlier, on October 14, 1929. She received her Airworthiness Certificate nearly a year later, and on October 5 crashed over France on her first scheduled overseas voyage, killing 48 (incl. Lord Thomson, the Air Minister). This effectively put an end to all airship aspirations in Great Britain. The Imperial Airship Scheme, developed and advocated by Thomson, was canceled.

Earlier, British Military experimented with airship-borne fighter planes. The idea of a flying aircraft carrier arised some serious thoughts stateside, and on October 31, 1929, the construction of the first carrier airship started in Akron, OH. The ship, appropriately named Akron (Navy designation ZRS-4,) entered service in October 1931. She carried four Sparrohawk biplane fighters.

![]()

USS Akron at NAS Sunnyvale, June 1932 (William T. Larkins collection via Telstar Logistics @ Flickr)

On April 4, 1933, Akron was lost over the stormy Atlantic. The accident left 73 dead (incl. Rear Admiral Moffett,) making it the deadliest air crash up to that time.

In a couple of months the U.S. Navy received a replacement: Akron‘s sistership Macon, built for the Pacific Ocean service. She carried five Sparrohawks:

![]()

(via fcarvallo @ Flickr)

On April 12, 1935, Macon was severely damaged and lost off the California coast. Most of her crew was saved. Together with her sistership, she was the largest helium-filled airship ever built.

Less famous and much more successful was the ZMC-2, world’s only successfully-operated metal-skinned airship.

![]()

ZMC-2 at Lakehurst, January 1935. Via RyanCrierie @ Flickr

Built by the Aircraft Development Corporation of Detroit in 1929, she was operated by the U.S. Navy until 1941. Nicknamed “The Tin Airship”, the ZMC-2 was constructed out of Alclad, an aluminum alloy clad with a very thin layer of pure aluminum. The Navy dismantled her after 752 flights (2265 hours of flight time).

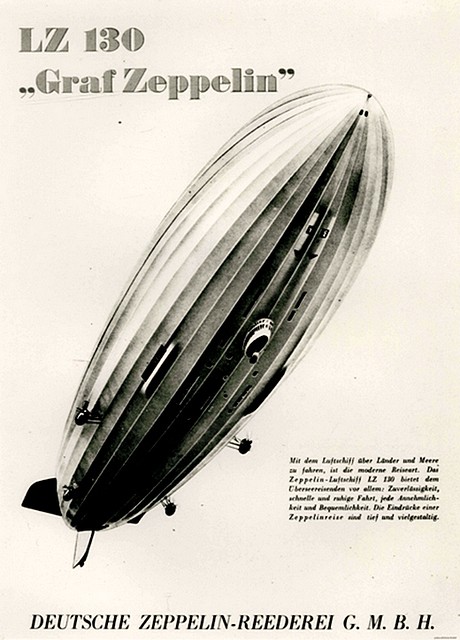

Maybe we should dedicate a special gallery to the U.S. Navy blimps and their WWII service. Right now, there is one more rigid airship to be mentioned – the LZ130 Graf Zeppelin II.

![]()

LZ130 and her commander Captain Sammt. Via lazzo51 @ Flickr

Commissioned in September 1938, more than a year after the Hindenburg disaster, she never entered the transcontinental passenger service. Instead, she was used for propaganda flights over Germany and recently annexed Sudetenland. In Summer 1939, the Graf Zeppelin II was sent on an espionage flight which wasn’t a success.

![]()

In April 1940 Hermann Goering, a renowned zeppelin-hater, ordered to dismantle the LZ130 together with her namesake, the retired LZ127. Zeppelin hangars in Frankfurt were destroyed by explosives on May 6 the same year, exactly three years after the Hindenburg was lost.

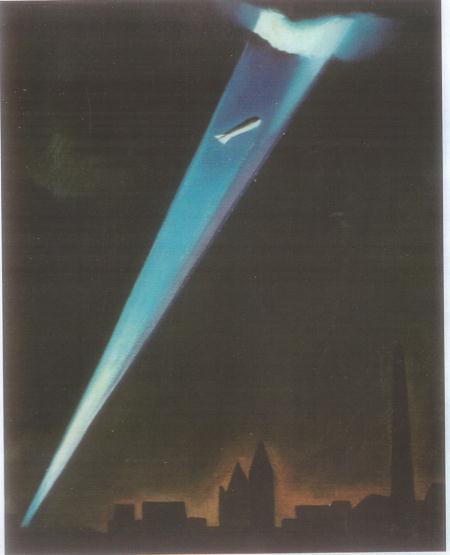

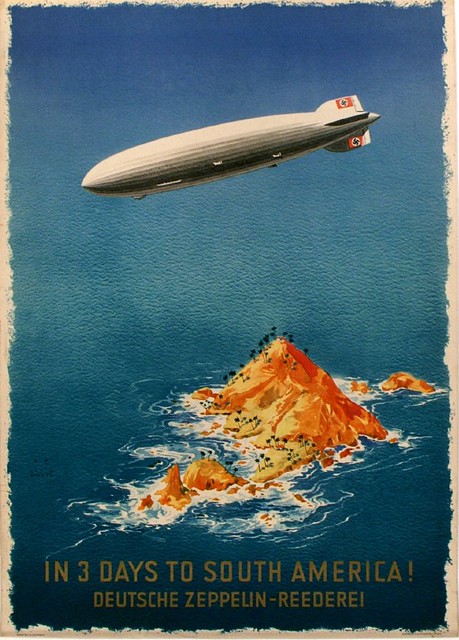

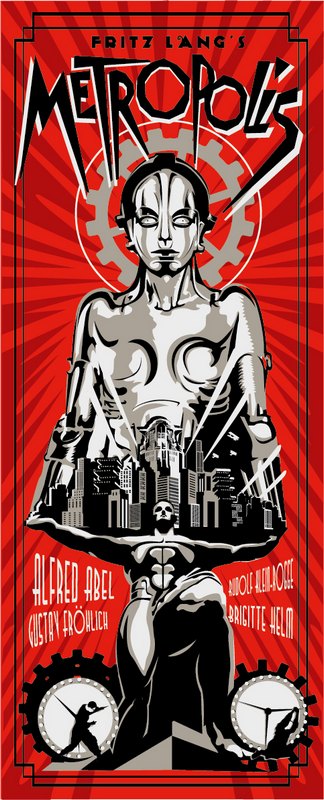

Now, some airship art:

![]()

Airship by RAM (Ruggero Alfredo Michahelles). 1927

![]()

Post Office mural by Peppino Mangravite. 1937

![]()

In Three Days to South America by Jupp Wiertz. 1936

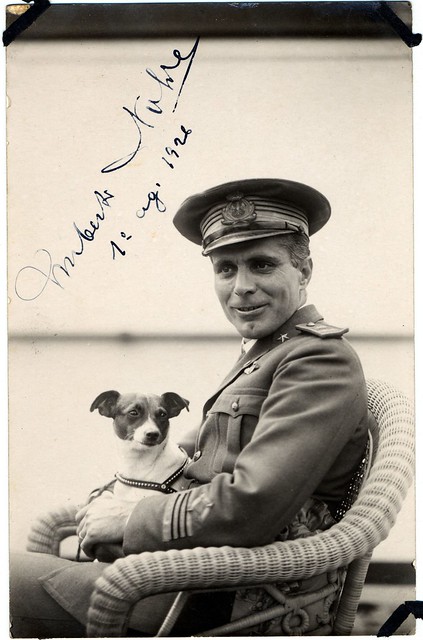

And some airship people:

![]()

Dr. Hugo Eckener. Via micky the pixel @ Flickr

![]()

Umberto Nobile and Titina. Don’t laugh: the little dog accompanied her master to the Pole in 1926 and survived the Italia disaster in 1928. Via AirSpace Blog (Smithsonian)

![Russian airship crewmen]()

Russian airship crewmen (left to right) – Nikolai Gudovantsev, Ivan Obodzinsky, Ivan Pan’kov and Vladimir Ustinovich. 1933 (E.M. Oppman archive)

![NPG 5464; Sir Barnes Wallis by Alfred Egerton Cooper]()

Sir Barnes Wallis by Alfred Egerton Cooper, 1942 (National Portrait Gallery)

![AdmiralWilliamAMoffett]()

Rear Admiral William A. Moffett

![]()

![]()